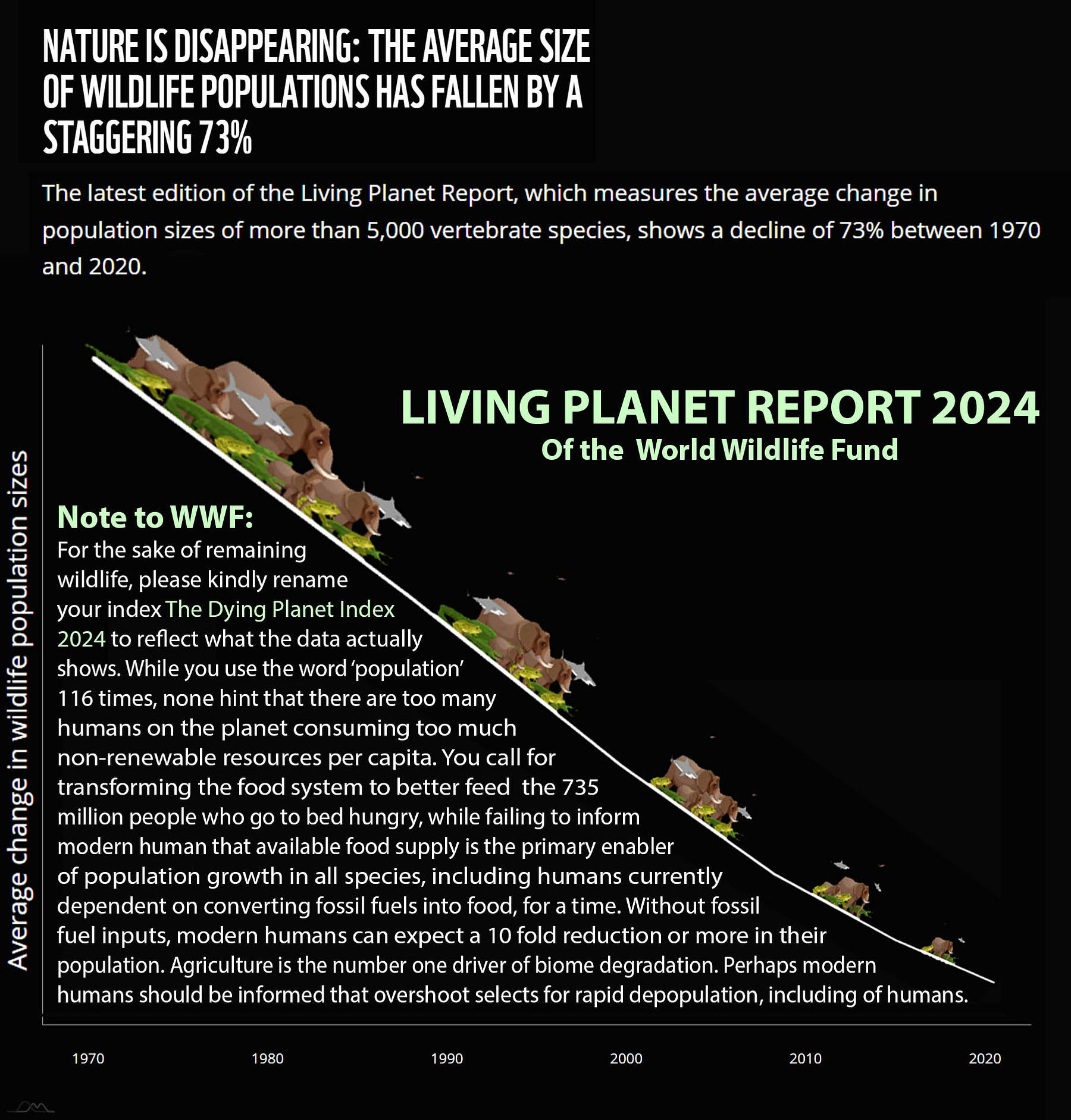

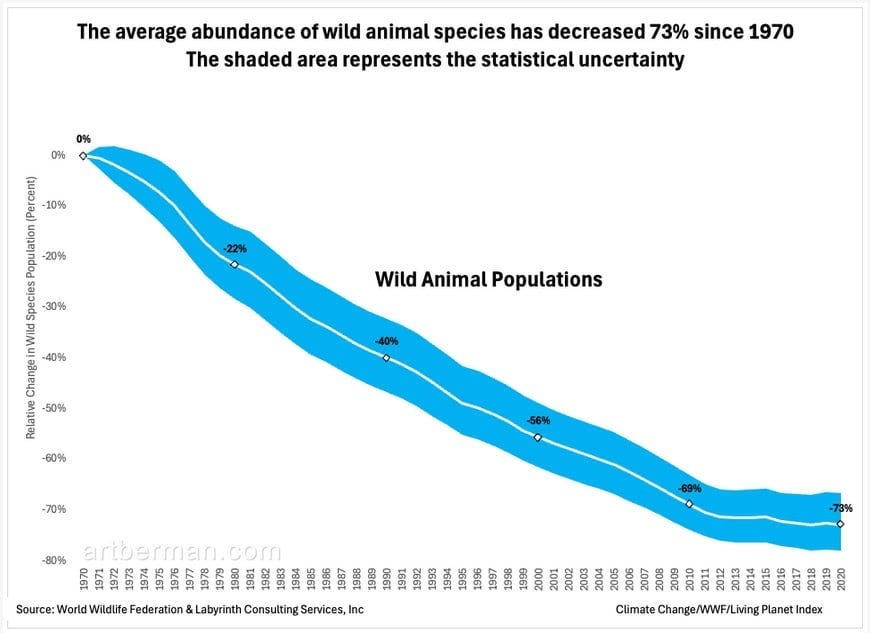

The World Wildlife Fund’s Living Planet Report 2024 notes that biodiversity is collapsing, and it’s hitting the most vulnerable ecosystems the hardest. The average abundance of wild animal species has decreased 73% since 1970:

The collapse of ecosystems, vanishing wildlife, and polluted waters are not acts of Nature or God— they’re direct consequences of our actions in dismantling a planetary life-support system.

Focusing on climate change, however, is a distraction. If we just capture the carbon pollution (somehow) we will be saved (not). Renewable energy will allow us to keep on growing, or not if we choose. We metastatic moderners ignore the deeper issue: overshoot — we have been exceeding the planet’s ecological limits regionally for millennia, and are now going a global overpulsing for the first time that will involve a global collapse.

The idea of a renewable-energy powered future that allows for economic growth is self and other terminating delusion — a death sentence for Earth’s ecosystems and posterity’s well-being. It reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of reality.

I was going to type more but Art Berman already has, see post Dark Matter: Unseen Forces Shaping Our Climate and Future, or read shorter version below.

We’re fixated on finding answers before we even understand the question, rushing to fix problems without taking the time to trace their roots. Real progress requires slowing down and placing things in a broader systems perspective. Tackling a small issue in isolation might feel productive, but it risks destabilizing everything connected to it.

The real problem lies in the way we think — that’s the true dark matter operating beneath the surface, shaping how we perceive and engage with the world.

“We have systematically misunderstood the nature of reality. Now we have reached the point where there is an urgent need to transform both how we think of the world and what we make of ourselves.

“The problem is that the very brain mechanisms which succeeded in simplifying the world so as to be subjected to our control, militate against a true understanding of it.”

The strategies that brought us success in the past won’t carry us forward. Like other alpha species before us, we’ve reached a threshold where failure to adapt could mean extinction. Climate change and overshooting ecological and energy limits are age-old stories — central to the collapse of most previous species and civilizations.

Humans thrived by breaking down a complex world into simple components, solving immediate problems without much concern for the wreckage left behind. When our population was small, the planet’s vast ecosystems could absorb the damage. But fossil fuels changed everything. Our numbers skyrocketed — from 2.5 billion in 1950 to over 8 billion today — and with them, our impact on the planet.

The trouble is that most of us don’t see how much this changes our present and future. We’ve become masters of dissection but lost sight of integration, mistaking precision for understanding.

“The isolated knowledge obtained by a group of specialists in the narrow field, has itself no value whatsoever, but only in its synthesis with the rest of knowledge, and as much as it really contributes in the synthesis towards answering the demand, who are we?”

This fragmented mindset blinds us to the bigger picture, where changes in one area ripple outward, disrupting systems we thought were separate.

A perfect example was adding lead to gasoline to solve the problem of engine knocking. It was a great short-term fix but its costs were staggering and we still haven’t recovered from the damage. No one stopped to consider that lead is a neurotoxin. It poisoned children, stunted brain development, and fueled crime through impaired judgment and impulse control. The damage extended beyond people — lead contaminated the air, soil, and ecosystems, leaving a toxic legacy in its wake.

We’re making the same mistake with our problem-solving approach to climate change. We’ve zeroed in on fossil fuel emissions as the problem and pinned our hopes on renewable energy as the solution. But we haven’t thought through how either the problem or the solution fits into the bigger picture — how shifting to renewables will affect the rest of our energy system or the stability of our society.

Renewable energy mostly generates electricity, which accounts for only about 20% of our total energy use. We tell ourselves we’re replacing fossil fuels, but we’re really just stacking renewables on top of oil, gas, and coal. Making matters worse, the material resources for renewables require vast amounts of minerals that are mined, transported, manufactured and distributed using fossil fuels. And most of those material resources will not last beyond the first generation of solar panels and wind turbines.

The result? Emissions keep rising, the economy keeps growing, and Earth’s ecosystems continue to unravel. Our best efforts to decarbonize energy will have little consequence unless we change our relationship to energy and to the natural world.

“It is hardly surprising, therefore, that while we have succeeded in coercing the world to our will to an extent unimaginable a few generations ago, we have at the same time wrought havoc on that world precisely because we have not understood it.”

Ian McGilchrist, The Matter With Things

Many see the developing world as the next frontier for economic and energy expansion. But, as Ray Dalio points out, earlier growth depended on vast, resource-rich lands in the Americas that allowed European powers to build wealth and industry. Without that natural abundance, empires like Britain and the U.S. could never have achieved dominance.

“European countries, western countries, have stabilized population, and the idea is, let’s just have that same thing happen for all the growing countries, like in Africa…The demographic transition worked for European and western countries because the context was an exploitable world that was not yet denuded.

“Where are the Africans going find their Africa, so to speak? Where are they going to find their exploitable, colonizable world of bountiful resources? It’s just not going to happen. You can’t just rinse and repeat.”

For those who believe technology and innovation have made resource-driven strategies obsolete, consider this: Why are China, Russia, and Iran still aggressively pursuing territorial expansion and resource acquisition?

The global order is unraveling under the combined pressure of energy limits and ecological overshoot. The conflicts in the Middle East, East Asia, and Ukraine aren’t just about political disputes — they’re battles over dwindling resources. As fossil fuels become scarcer and energy returns decline, the world’s great powers are locked in a scramble to secure what remains. This struggle isn’t just a temporary crisis; it’s the defining feature of a post-growth world where energy constraints will set the limits of economic and political power. Without access to abundant resources, growth stalls, forcing nations to compete in increasingly zero-sum terms.

“So the world starts to shift and change quite dramatically. Sides start having to be taken. Bamboo curtains and iron curtains start going back up between who does and doesn’t trade with each other. And so there’s a geopolitical kind of threshold to this as well, which doesn’t sit well when you’re thinking about the earth as a single entity biologically, and how you cooperate and collaborate across international borders to try and get the best of all outcomes.

So it’s quite frightening to think of it from a one world perspective

It doesn’t have to be this way, but we won’t problem-solve our way out of these geopolitical, climate, and ecological overshoot crises. There’s no silver bullet — technology alone won’t save us. The path forward requires a deeper transformation in how we imagine and engage with the world. The reductionist mindset that got us here — treating the planet as a collection of resources to exploit — must give way to a new way of thinking.

The real frontier is psychological, and it won’t be crossed easily — or willingly. The first step toward a different future is recognizing the gravity of the challenges we face and understanding that these problems are systemic, not isolated. The solution isn’t about fixing individual parts but shifting our focus toward adapting to the whole — seeing how everything is interconnected.

We need to confront the hard truth: we may no longer be able to fix what’s broken. The time for easy solutions has passed. Now, the real work lies in mitigating damage and adapting to what’s already inevitable because we waited too long to act. Without this shift, we’ll keep chasing unsustainable growth, piling on new problems as we try to outrun the crises we’ve set in motion. It’s time to let go of the illusion that we can “solve” everything and start focusing on how to live within the limits we’ve already crossed.

We need to grow up as a species and start treating Earth like the home it is — because it’s the only one we’ve got. There’s no escape hatch, no backup plan — just this one fragile planet, and it’s time we start acting like it.

Our survival depends on recognizing that we are part of, not separate from — the web of life and the systems that sustain it. If we don’t, we’re only accelerating our own decline.

Eric Lee